Location:

PMKI > Organizations

& Governance > Complexity & Mega

Projects (and Programs).

- Complexity Theory

- Complex Project (and Program)

Management

- Megaproject Issues and Challenges

- Useful External Web-links &

Resources.

Other related sections of the PMKI:

- Scheduling Complexity & Mega Projects

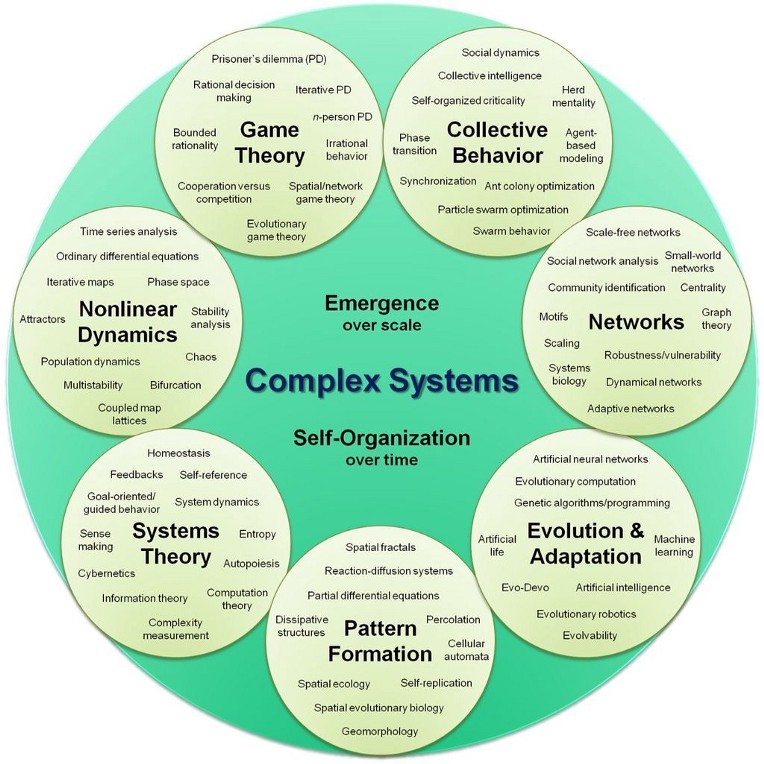

Complexity theory is a science that recognizes and

celebrates the creativity of nature, it opens the door to

a new way of seeing the world, recognizing that complex

dynamic systems (both natural and man made) are sensitive

to initial conditions and have emergent properties. While

we can influence them, we cannot control them.

Complexity theorists are interested in the relationship between apparently ordered systems and their underlying instability and the rules that govern apparently chaotic behaviors. For example, shoals of fish and swarms of ants appear chaotic, but the way they behave is based on a set of very precise rules. Whereas chaordic systems exhibit a degree of predictability at their higher levels but are completely unpredictable at the detail level. Examples include the weather and projects. Most human organizations, including businesses and project teams are chaordic in nature.

When considering systems, complexity is not a synonym for big or complicated. Some complicated systems are stable and predictable, others are inherently complex. Whereas some small systems can be very chaotic. The sciences of complexity are a variety of process-oriented areas of research exploring non-linear dynamics within complex systems including interconnectedness, unpredictability, and uncontrolability, which are all key characteristics of all complex dynamic systems such as a project team, these are the focus of the papers below.

WP: Complexity Theory. Complexity theory helps understand the social behaviours of teams and the networks of people involved in and around a project.

PP: A Simple View of ‘Complexity’ in Project Management. This paper traces the development of ‘Complexity Theory’ from its origins in Chaos Theory and links the theory to modern project management and seeks to link the ideas within two other strands of research; ‘Social Networks’ and ‘Temporary Knowledge Organizations’, to Complexity Theory. Complexity theory helps understand the social behaviours of teams and networks of people involved in and around a project. The ideas apply equally to small in-house projects as to large complicated projects. In this regard, ‘complexity’ is not a synonym for ‘complicated’ or ‘large’. This paper briefly examines the underlying ideas and philosophies that have created ‘modern project management’ together with some emerging ideas such as projects being ‘temporary knowledge organizations’ (TKOs) [See also: The Origins of Modern Project Management]. From this theoretical framework the true nature of a ‘project’ is described from the perspective of the ‘knowledge workers’ or ‘actors’ engaged in the creation, execution, delivery and closure of the project. Then two critical aspects of project management practice will be re-evaluated from a ‘complexity’ perspective.

Art: Avoiding the 'Tipping Point to Failure'. Increases in project complexity are predictable and manageable until the tipping point is reached. After the tipping point, the situation flips from predictable and manageable to chaotic and unmanageable within the current context.

Art: Controlling Complex Projects. Complexity is not a synonym for complicated or large is just one of the dimensions inherent in every project and has to be managed properly.

Blg: Poor Governance creates complexity. Poor governance allows ineffective management which creates unnecessary ambiguity and complexity in projects.

Blg: Stakeholders in complexity. The effect of stakeholders on complex project management and the work of the ICCPM.

Art: Stakeholders and Complexity. Project ‘control systems’ don’t control anything and to a large extent, neither can project managers.In the complex world of the 21st century, communicating to influence outcomes is the key to success.

Blg: Complicated vs Complex – Understanding Complexity. Estimating, planning, and managing a complex project requires a different approach. This post looks at some of the key differences in managing a complicated project and managing a complex project.

DP: Complex Decision Making. Many aspects of project management involve making complex decisions - this CSIRO paper provides valuable insights into how people make complex decisions.

Prs: Risk Management and Complexity Theory - The Human Dimension of Risk. The outcome of projects is always uncertain and risk management has become a ‘hot topic’ in recent years. However, despite all of the interest, risk management remains one of the least appreciated aspects of modern management. Whilst arguably the key competence (or competitive advantage) of every organization is its ability to effectively manage the risks inherent in its environment; most organizations are excessively risk averse, and in their attempts to avoid ‘all risk’ expose themselves to more adverse outcomes than if they actively embraced and managed risk. No client can avoid the ultimate risks associated with its project such as the liquidation of its prime contractor; these major events inevitably impact the client and by attempting to quarantine itself from ‘all risk’, the client simply passes the benefit of any favourable outcomes to its contractor. Within this framework, ‘Complexity Theory’ helps us understand the social behaviours of teams and networks of people involved in and around a project. This paper briefly examines the development of ‘Complexity Theory’ from its origins in Chaos Theory to the ideas of ‘Complex Responsive Processes of Relating’ (CRPR) and seek to link the ideas within Complexity Theory to the practice of risk management so as to develop an understanding of risk and uncertainty from the viewpoint of complexity theory. The paper then describes the key aspects of risk management from the human perspective, with a view to optimizing the overall risk management for a project and its host organization. Particular focus is on the risk attitudes and competencies required at each level of management to optimize risk. The paper concludes by developing a range of practical suggestions for improving the effectiveness of risk management practice within projects based on an understanding of ‘complexity theory’ applied to the project environment.

PP: Scheduling in the Age of Complexity. This paper suggests that a radically different approach is needed to make scheduling relevant and useful in the 21st Century. Starting with the ideas derived from Complexity Theory, Complex Responsive Processes of Relating (CRPR) and the concept of the project team as a ‘Temporary Knowledge Organization (TKO) one can see the delivery of the project being crafted by thousands of individual decisions and actions taken by people who are ‘actors’ within the social network of the project team and its immediate surrounds. The role of ‘project management’ is to motivate, coordinate and lead the team towards the common objective of a successful project outcome. The project scheduler has a key role in this complex environment provided the right attitudes, skills and scheduling techniques are used in the optimum way.

Art: Radical Uncertainty. Making predictive models more mathematical does not improve the accuracy of the predictions, a different paradigm is needed in a complex world.

Prs: Avoiding the 'Tipping Point to Failure'. Delivering ‘on the promise’ to meet client and stakeholder expectations requires project organizations that are capable of accomplishing the work! Whist this statement is obvious, most organizations remain blissfully unaware of Gladwell’s tipping point. The tipping point marks the boundary between linear changes and catastrophic change and unfortunately, it is impossible to predict where a tipping point may occur until after it has been reached.

The reason this is an important consideration for all project managers and project organizations is that leading up to the tipping point, increases in project complexity have predictable increases in difficulty and the situation is manageable. Once the tipping point is reached, the situation flips from predictable and manageable to unmanageable within the current context. New paradigms are needed to first stabilize the situation, then recover. But there is no fixed point for the change; the tipping point is influenced by the capability of the performing organization and its people and the degree of complexity of the work they are asked to accomplish.

The degree of complexity associated with the work of the project increases exponentially and is influenced by a combination of its inherent size, technical difficulty, intensity, and the surrounding stakeholder relationships. Each performing organization can manage a level of complexity based on its prior experience, maturity, supporting systems and the capability of the people managing the work. As long as the ‘complexity’ is within the management capability of the organization and the people it deploys, reasonably predictable outcomes can be expected and normal risk management practices are likely to be effective. Change any of these parameters to the point where the overall tipping point is reached and there is a sudden breakdown that causes a significant negative change in the likely project outcomes. Recovery is no longer a simple process of marginally increasing the resources deployed, what’s needed is a massive change in the capability of resources.

This presentation:

- Explores the concept of a ‘complexity quotient’ and

identify elements that are controllable by the

organization such as optimizing the amount of

information in the project control systems.

- Examines the concept of the tipping point and highlights

the role of project 'control' systems in

identifying potential early warning

indicators that may be used to see the 'tipping point'

approaching.

- Considers how an organization can deal with a project

that has ‘tipped’ either as the consequence of

an unforeseeable event, a ‘black swan’, or

through an inexorable build up of complexity within the

work.

- The concept of organizational resilience is defined.

The tipping point is not fixed for any organization, by developing improved systems and acquiring experience the organization can grow to be capable of managing larger, more complex projects. The challenge is to achieve this growth without running into a tipping point.

Click through for more on Scheduling Complexity & Mega Projects

Blg: Differentiating normal, complex and megaprojects. A look at the additional layers of competency needed to manage complex projects and megaprojects and a suggested framework for classifying these different types of project.

The International Centre for Complex Project

Management (ICCPM), Complex Project Leadership

Competency Standard defines a performance-based competency

framework, identifying the skills and competencies project

leaders need to succeed in complex environments.

Download from: https://iccpm.com/resource-centre/complex-project-leadership-competency-standards-2023/

The

Cynefin Co was founded in 2005 by Dave Snowden to

build methods, tools and capability that apply the wisdom

from Complex Adaptive Systems theory and other scientific

disciplines in social systems.

The

Cynefin Co was founded in 2005 by Dave Snowden to

build methods, tools and capability that apply the wisdom

from Complex Adaptive Systems theory and other scientific

disciplines in social systems.

The Major Projects Knowledge Hub - Lessons learned

from major projects in the UK - https://www.majorprojectsknowledgehub.net/

For papers on Complexity & Mega Projects presented

at the PGCS Annual Symposium see:

For papers on Complexity & Mega Projects presented

at the PGCS Annual Symposium see: